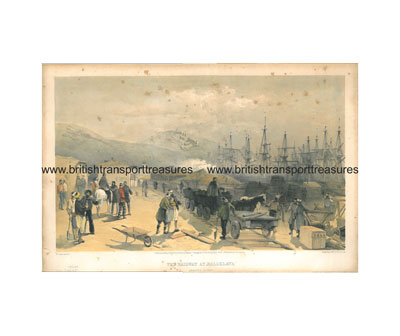

Description

What is a lithograph of “The Railway at Balaklava” doing in British Transport Treasures? The answer lies in the brand on the box in the bottom right hand corner – “PB&B” Peto, Brassey and Betts — probably the greatest British civil engineering contractor’s partnership of the century. By the winter of 1855, the British and French armies besieging Sevastopol were in a poor state, due to military reverses, bad weather, sickness and supply problems. The muddy tracks leading to HQ and the front line became impassable for wheeled traffic, every single item had to be moved by pack animals or on the worst pitches, hand to hand in a human chain.

News of these conditions was relayed to Britain, mainly by William Howard Russell, special correspondent of The Times. Not for the last time, Government ill-preparedness in time of war, exacerbated by military incompetence was to be rectified by outstanding civilian effort. Hearing the news, Samuel Morton Peto, one of the leading railway contractors of the day, offered with his partners Edward Betts and Thomas Brassey, to build at cost, without any contract or personal advantage, a railway to transport supplies from the port of Balaclava to the troops outside Sevastopol. They promised to have a railroad at work in three weeks after landing at Balaclava. The offer was accepted and the Betts played a leading role in obtaining supplies (including rolling stock, rails and sleepers, also at cost price from the stocks of the leading British railways, there being no time to place contracts for rails to be rolled to order). Arrangements were made to purchase or hire 12 ships, and to recruit engineers and navvies. The fleet set sail on 21st December and arrived at the beginning of February

The first task was to create a quay at Balaclava where the railway materials could be unloaded, with a yard adjacent. The track was to pass along the middle of the main street of the town. It then went through a gorge at the north of the town close to the water’s edge and over boggy ground to the village of Kadikoi. From here, the railway had to rise some 500 feet (152 m) to the top of the plateau. Of the routes available, it was decided to follow the existing road, although in parts it was as steep as 1 in 7. A deviation found a route with a maximum gradient of 1 in 14. A stationary engine would be required at the top of this stretch to pull the railway wagons up the incline. Once on the plateau, the ground was rough but fairly level and here it presented fewer problems. Lord Raglan’s headquarters were at the top of the col, and it was decided that a depot should be constructed here.

Within three weeks of the arrival of the fleet carrying materials and men the railway had started to run and in seven weeks 7 miles (11 km) of track had been completed. The railway was a major factor leading to the success of the siege. After the end of the war the track was sold and removed.

The date on the print is that of publication not of the scene depicted, which is looking south down the village street towards the harbour. In the lithograph process the artist had to draw his work direct onto the “stones” used for printing. Given a voyage of around five weeks back to England and say a week to prepare the plates the scene cannot have been later than mid April. However the railway was said to be in operation by the end of March and in this scene is plainly still under construction with temporary track and contractor’s wagons drawn by horses.

In recognition of his contribution to the war effort Peto was created Baronet.

Of related interest

We will shortly be makng available the classic biography

The Life and Labours of Mr. Brassey

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.