Description

n the days when the majority of railway carriages were of the separate compartment type, rather than the open saloons of today, the only alternative to looking out of the window to making unwelcome eye contact with the strangers opposite, was to stare at the luggage rack. A number of railways adopted the scheme of displaying two or three sepia photographs of places served by the line in the space between the opposing passenger’s heads, and the luggage rack. These were of the “Promenade at Cleethorpes” variety, and were still in situ in elderly carriages, long after the straw boaters and long dresses of the figures depicted had ceased to be fashionable. Between the Wars, attractive water-colours of villages, landscapes and historic buildings were commissioned from well-known artists for use in new rolling stock.

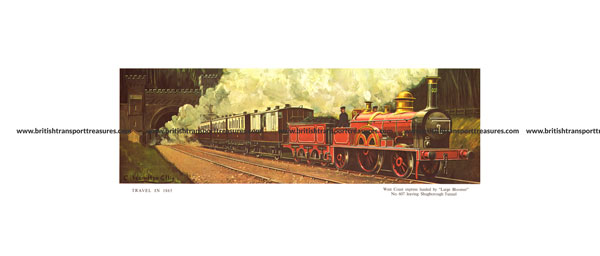

However, apart from the occasional viaduct, few were of direct railway interest. Around 1950, George Dow, P.R& P.O of the London Midland Region, and already a noted railway historian, decided to brighten up travel in bleak austerity Britain, by commissioning railway author and artist Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis (1909-1987) to produce 24 oil paintings on the theme of “Travel in…” featuring colourful trains and ships which had belonged to companies swallowed up in the former London Midland & Scottish Railway in 1923. This, featuring a scene in 1865, was No.8 in the series.

Hamilton Ellis was a good historian who, (unlike some of his contemporaries who could have qualified for a “Queen’s Award for Re-cycling”) undertook a great deal of original research.

But He was sometimes a little out of his depth when dealing with the LNWR. According to ”Locomotives of the LNWR Southern Division” by Harry Jack, the first of James McConnell’s “Large Bloomers” appeared in 1851, (the name will be explained shortly) They were larger engines than had been in common use on the Southern Division, with 7ft driving wheels, and attracted considerable attention. The name “Bloomer” was at first a nickname, but was quickly adopted officially. The nickname was a topical one in the autumn of 1851 when the first engine arrived on the line, because of the current popular excitement aroused by the appearance of women wearing trousers, as advocated by a noisy American propagandist, Mrs. Amelia Bloomer. Sixty were built, They were numbered 247–256, 287–296 and 389–408, until 1862 when they were renumbered by the addition of 600, becoming 847 (etc.) to 1008.

Eleven smaller examples (logically “Small Bloomers) were built in 1854 with 6ft 6ins driving wheels intended for secondary fast main-line trains and branch lines of the Southern Division. These engines were originally intended by McConnell to be a 7 ft.-wheel variant of his Patent class, but the design was altered by order of the directors to a smaller version of the successful Bloomers. Numbers originally carried were an assortment from 2 to 381, renumbered 602 (etc. including 607) up to 981 in 1862.

As for the three “Extra Large Bloomers”, with 7ft6ins. driving wheels built in 1869, they need not detain us further. They were more than 1.5tons over their designed weight and scarcely turned a wheel in service before they were withdrawn because of track damage.

An enduring myth is that until 1862 the Bloomers (and other Southern Division engines) were painted vermilion. They were not, although some were painted a very dark plum-red from 1861, before the standard livery reverted to green in the following year, and then changed to black from 1873.

So “Travel in 1865” is an imaginary scene. The locomotive depicted is indeed a “Large Bloomer” but the number 607 belonged to a “Small Bloomer”, neither type locomotive would have been painted this shade of red at any time, and in 1865, both would have been green.

In fairness to Hamilton Ellis, much of the above information has only come to light in recent years. If not strictly historically accurate, the painting can at least be enjoyed as a spirited rendering of travel at this period. I wonder if the artist was already mulling over a little joke which appeared in his later writings. “There was no more stirring sight than a pair of Large Bloomers on the front of the Down Irish Mail!”

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.