Description

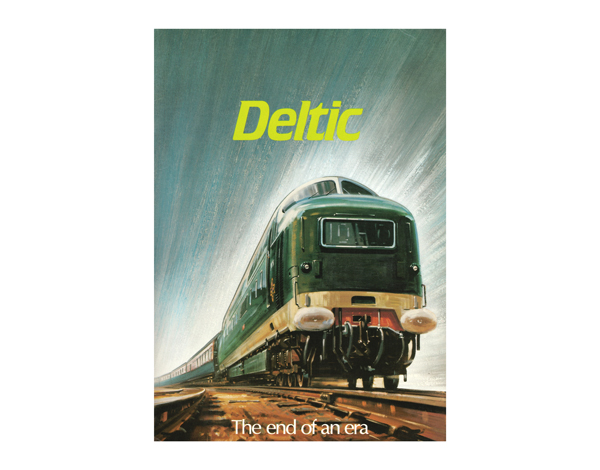

As a lover of the steam locomotive, I have never been a great fan of diesel electrics. The smellof the fumes in carriages, before air conditioning was introduced, could be nauseating, the unreliability of their train heating boilers could make winter journeys a misery, and the blue livery which they casrried for much of their working lives was just plain horrible, once it began to wear thin. I did make an exception for the Deltics ,however – I almost regarded them as “Honorary Steam Locomotives!” Also we began our railway careers at much the same time, although I lasted a bit longer that they did…

In1946/7 the LNER formulated a proposal for 25high powered diesel-electric locomotives to replace “Pacifics” on Anglo-Scottish services. Under nationalisation, the proposal was put forward by Eastern, North Eastern and Scottish Regions for a similar scheme to the Railway Executive. There was at the time no suitable prototype available The LMS “TWINS” were not powerful enough and were up to the limit so far as axle loadings were concerned, and lighter weight diesel engines and generators were required to fit within the British loading gauge. The Railway Executive member for mechanical engineering, R.A.Riddles had no time for diesel traction (other than shunters)and dismissed the proposal out of hand. A great opportunity was lost, and several years and millions wasted, before the private sector solved the problem.

In fact the initial breakthrough was made in Germany where the aircraft manufacturer Junkers developed the Jumo 204 Diesel aeroplane engine, an opposed-piston two-stroke design. Instead of each cylinder having a single piston and being closed at one end with a cylinder head, the Jumo design used an elongated cylinder containing two pistons moving in opposite directions towards the centre. This negated the need for a heavy cylinder head, the opposing piston filled this role. On the downside, the layout required separate crankshafts on each end of the engine that must be coupled through gear.. Before the war, Napier had been working on an aviation Diesel design known as the Culverin after licensing versions of the Jumo204. The Admralty had a requirement for a comparatively light diesel engine to power motor torpedo boats, British ones being petrol fueled were much more vulnerable than the equivalent German craft. The Admiralty required a much more powerful engine, and knew about Junkers’ designs for multi-crankshaft engines of straight six and diamond-form and felt that these would be a reasonable starting point for the larger design which it required. The result was a triangle, the cylinder banks forming the sides, and tipped by three crankshafts one at each apex. These shafts were connected with phased gearing to a single output shaft. Sounds simple, but a cut away model of a Deltic engine reveals gear trains of mind boggling complexity. The Admiralty placed a contract with English Electric, who had taken over Napier, and the rest as they say is history. It was an act of genius to place two of these immensely powerful engines in a locomotive, driving generators to power traction motors. The resulting machine was for a time the most powerful single diesel electric unit in the world. It took nearly ten years of development to reach this stage, all at the financial risk of English Electric. While the former Napier works built the engines, the prototype locomotive was assembled at the former Dick Kerr tramcar works at Preston. But who on earth decided to turnout the prototype in a livery which would not have looked out of place on a fairground dodgem car? Compared to the dignified austere black and silver of the LMS Twins 10000 and 10001, it looked rather silly.

As Public Relations Officer of the former Eastern Region, I played a minor role in the later part of the Deltic story. On 27 February 1982 I arranged a brief handover ceremony at York station, when D9002 The King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was donated to the National Railway Museum, where it is preserved in working order. The Friends of the National Railway Museum paid for restoration of the original two tone green service livery. The lighter green was originally chosen by design consultants “to disguise the bulk of the locomotive”. Why?The Deltic was a large powerful brute of a machine, why try to pretend otherwise?

I wonder how many people nowadays appreciate the coincidence of the initial letters KOYLI and the name of the then Keeper of the National Railway Museum, the late Dr. John Coiley, a true gentleman whom I met on his first day occupying a Portakabin on the Museum site, and had the pleasure of a friendly working relationship over many years.

PREVIEW BELOW – MAY TAKE A WHILE TO LOAD.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.